17-Mile Village

17-Mile Village: our fifth clinic

By Jane Lillian Vance

I. The Journey

When OMNI leader Karen Throckmorton clinks her fork to her water glass at the breakfast table, and Chief of OMNI Security Derrick Kalinda stands up to speak, the team knows that we are in The Situation Room.

Derrick with his amazing subwoofer voice seriously instructs each of us to remain especially alert all day, always to have an armed security guard accompany us to the toilet, and to report even the slightest suspicious activity directly to him.

Derrick had of course scouted in advance this new clinic area for us. Still, his announcement this morning about a state of high alert includes admonitions for us to respond IMMEDIATELY, should Derrick need to instruct us to get back on the bus NOW, and to close ALL bus windows IMMEDIATELY.

These somber cautions partly reflect the fact that 17-Mile is a new clinic for us, first time, and we are routinely, but especially on such a day as this, prudent.

More, the concern derives from the fact that this new area gets its name from being 17 miles south of Mufulira, the mining town on the literal border with the Congo.

At the enormous Frontier Mine there, and from even under our feet in our clinic under the old 17-Mile mango trees, come heaps of diamonds, gold, and copper.

For all the ages it has been true: in a poor land, wherever priceless treasure can be scratched from the soil, Three insatiable Monsters—Greed, Anger, and Desire—stir to power in human blood.

The Three Monsters harmonize, and sing sickening blood songs:

At any cost, steal the diamonds!

No matter how, get the gold!

Through any method, find the copper!

So today we must watch carefully for the telltale eyes of those men whose hearts are dancing to these songs of the Three devilish Monsters.

As for the route even to reach 17-Mile, 38 of us on our crammed bus—security guards, OMNI teachers (serving as our excellent translators), and those of us on the medical mission team—passed Ndola’s Levy Mwanawasa Football Stadium at 8:15 a.m. By 9:15, we are lurching and swaying through a bone-dry eucalyptus plantation, thousands and miles of slender trees equally erect in military formation, their trunks peeling and oozing crimson sap. Something glints: MAINTAINED BY CASA FARMS, a small metal announcement staked somewhere in this disturbingly barren forest boasts for a moment, to absolutely no one.

Sometimes, our view of the trees out the bus windows is occluded by closer giant roadside scrums of dusty lantana. On each side of the bus, our wheels churn enormous clouds of yellow and orange grit. Close the windows, though, and we suffocate in the metal box. As we go, we bump so violently that one of us leans her head out unsteadily and dry-heaves until she is too weak to stand.

In other words, 17-Mile isn’t easy to reach.

Giant termite mounds as large as a house rise like broken Sphinxes all around us, askew in the fields near us.

I consider these forms.

They do not seem to be sleeping.

A moment later, we pass a tiny cinderblock home, inexplicably placed near nothing at all, its single brown goat snorting dust as it leans against a small white satellite dish perched like a tedious postmodern proclamation on the dirt courtyard.

Now, we pass a huge metal sign for another mine, AVC International Holding Corporation Mining Company, lettered in Mandarin also. And then, we traverse barren stretches, landscapes hard to read and vaguely dangerous, punctuated on one side by flat-topped acacia trees, more typical of a lullaby landscape, like a Kenyan savannah; and on the other side, by a frighteningly long and very likely radioactive slag tailing, a miles-long grey python of ugly mining leftovers. Gil Harrington comments that, in one way, the endless slag tailing sweeps in length like a Blue Ridge vista, but no majesty dares inhabit this disaster.

Diamonds.

Gold.

Copper.

They are already whispering seductive promises from under our wheels.

We pass a metal cell tower, incongruously painted red and white. A surreal peppermint Eiffel Tower.

On this treacherous, tortured trail, dry as lost memories, we feel (ironically) as though we are tossing in a stormy ocean of earth.

Nurse Sunny conjures the watery Biblical passages around baby Moses, musing that we all typically gloss over his story, smiling as if his reedy ride down the Nile had been a liquid catwalk.

Communally, in our roiling bus, we consider the agony of that parent setting baby Moses afloat, releasing certainty, surely a miraculous act of placing faith over attachment.

II. The Clinic

After some dry hours, we arrive. We have reached 17-Mile.

Something resembling a sun-bleached, oversized Easter basket strikes me first, which a child could sleep in, hangs overhead, like an odd cradle in the koatapela (avocado) tree.

This basket is the winter roost of 17-Miles’ chickens, since, I’m told, the winter soil here hosts diseases which kill those chickens who sleep on the ground. Are there also other predators here who might attack the chickens at night?

“Yes, Madam, there are such problems. There could be hungry rats, or devious snakes. But the likeliest nocturnal villain is the impaka.”

Smaller than a lion, but larger than a house cat, and as variously pied in its coloration as zany hyenas, the impaka can smell the sleeping chickens and climb skillfully to snatch sleeping foul.

When I bring pink slips—completed patients’ records—to the collection bag—I mention the surprising idea of an impaka to Chriss Ross and Linda Hinson, who are virtually juggling prescriptions in Pharmacy—their hands are dispensing medicine so expertly.

Chriss’ response surprises me. “Yep, I’ve seen one. An impaka,” she nods, “on a previous trip. A little girl named Blessing was in her circular thatched home, tending to the charcoal fire. With a long wooden spoon, Blessing was stirring a very large cooking pot, and I looked to see what she was cooking. The pot featured a skinned and brothy impaka.”

Reveries are suspended when Lisa asks if I will gather humanitarian aid for a patient named Alice. Her name is pronounced al-EEEE-say. I gesture for her to sit with me in Wound Care. I read Intake’s notes. Alice is a case of GBV. She has suffered Gender-Based Violence.

I see a thing on Alice’s forehead which disorients me, which looks like a perfect third eye, dark black and possibly made of hair.

It isn’t. It’s a horrible split gash from a fist punch to her face, courtesy of her violent husband, who has been beating then raping her for years. Her arms and forehead are covered in scars. Today, her ribs may be fractured. On the head wound, she has placed a black herbal powder which acts like a desiccating charcoal. Alice, with her black third eye, sits in stony shock.

But before we can help Alice, Doc Margaret calls some of us over quickly to address 44-year-old Muzinga. “Her blood pressure is 260/180. She has suffered a right-side stroke and is incontinent. She is weak. I am worried about her.”

Judging by Doc Margaret’s jaw, “worried about her” = Muzinga could die, right now.

So we ply Muzinga with rehydration vitamins & electrolytes mixed into the rarest of commodities: clean water. She dosed her with antihypertensive medicine. We prepare a comfortable cot for her to rest on. We tell her about all the supplies we have gathered for her including blood pressure medication and transport to the local clinic, which strengthens and calms her condition. Her blood pressure, checked every five minutes, drops and stabilizes.

Meanwhile, Wound Care Lead and Freestyler, Gil Harrington, has been doing her thing. In ten short minutes, Gil has taken a surgical gown and honest-to-god fashioned it into a pair of wearable water-resistant pants WITH an adjustable drawstring. This invention alleviates Muzinga’s urinary incontinence.

Absurd. Impossible. It’s the best functional origami I have ever seen.

Muzinga, almost expired in our clinic, is now feeling better, up and surrounded by a pack of strong women, sisters and neighbors. They act like sentient bees.

Before she leaves, we size crutches for Muzinga, and she likes them. She starts to smile. She looks 44 years old again instead of 88. Her friends, her sisters, are humming around her.

How will she get home?, we ask.

Us, they declare.

The oldest of them taxies up an ancient bicycle, capable as an Olympian, and then, Muzinga’s womenfolk lift her torso onto the back of the bike. And the hive lifts and carries her legs, meanwhile also carrying our rice and salt and vitamins and medicine and washcloth and soap and a dozen other gifts, preparing to peddle Muzinga home.

I have seen this tableaux before.

I recognize this composition.

Muzinga’s sisters are in the exact positions of the soldiers from the iconic photograph taken by Joe Rosenthal on February 23, 1945, depicting United States Marines raising an American flag atop Mount Suribachi.

Muzinga is like the American flag in that image.

She is being lifted, raised, born again.

It is women who are lifting her.

Now it is time to meet Team Leader Karen and her interpreter and Zambian Security Guard who have come and knelt respectfully before this beautiful woman—in shock—sheltering in Wound Care: Alice, 32, about to break out of her cocoon.

Karen asks such tender questions.

When did this happen? Last night.

Has it ever happened before? We learn that Alice’s husband has beaten her countless times, through the years. Alice makes the sign of a menacing, punching fist.

Have you ever thought of reporting him before? Yes, but I always felt sorry for him, knowing he would get in trouble.

Do you have children?

Alice hardens, like she is going to explode. Yes, many. Seven children. But only one is alive, a 12-year-old girl.

How did the other children die?

Alice tenses.

Again she mimes a furious fist, punching.

Do you mean he brought about the death of six of your unborn children?

Yes.

Have you thought about what you want to do?

Alice nods. I have thought about ending this marriage.

And what are your impediments for acting on this thought?

Kwacha. I don’t have the money to leave.

How much would that take? Six dollars.

We can help you with that.

Later in the interview, 81-year-old gynecologist Dr. Henry comes into Wound Care.

One of the greatest pleasures of my life was listening to him address this beaten woman.

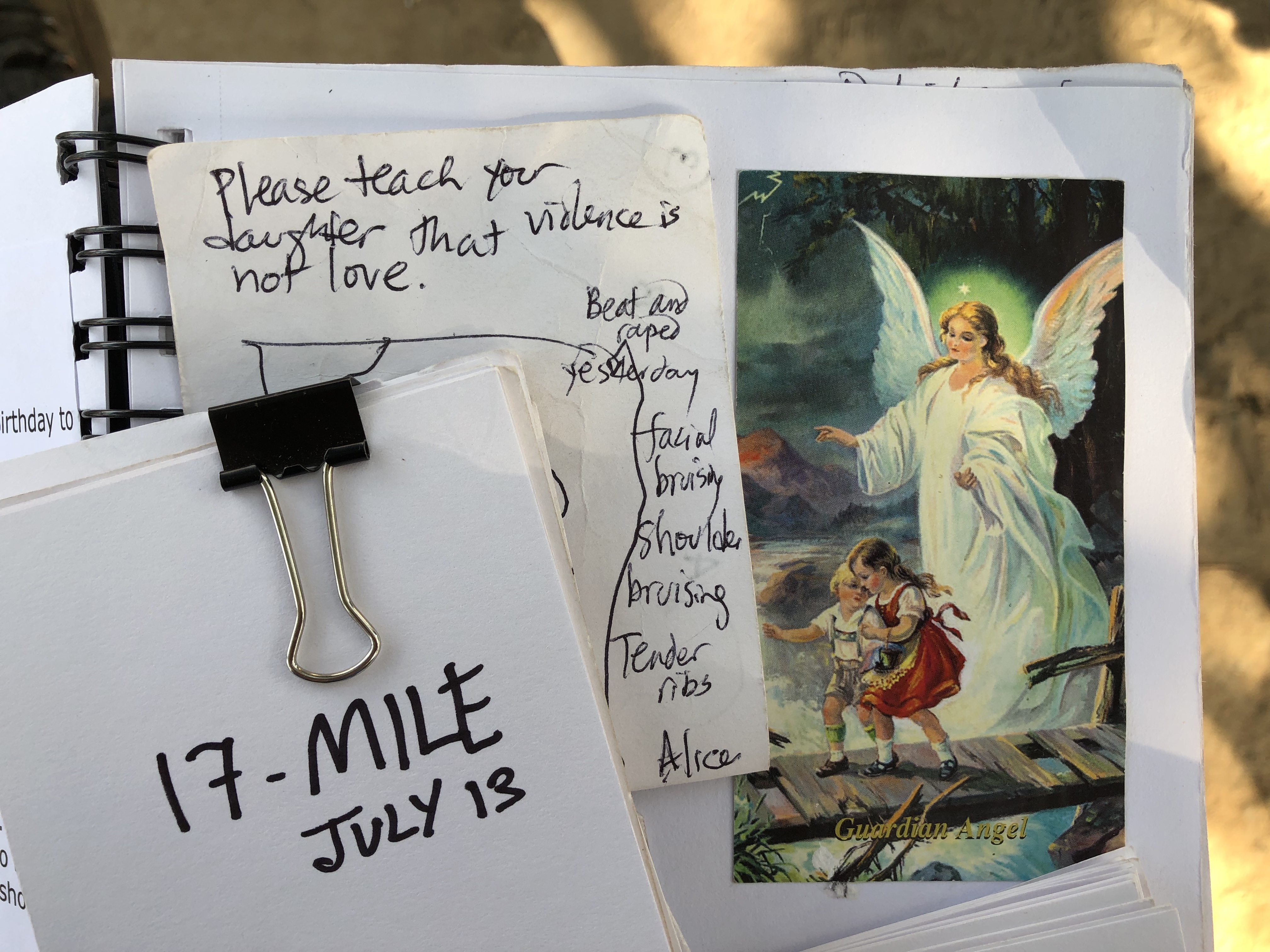

On an index card, in shaky, emotional writing, I memorialize part of what Dr. Henry says to Alice. He told her: SAFETY FROM VIOLENCE IS A UNIVERSAL HUMAN RIGHT. The beating, and the rape, were not mistakes or bad actions. They were CRIMES.

“I am concerned that your daughter has seen her father hurt you,” he said. “We are going to get you and your daughter out of his reach. I congratulate you on your courage. You have chosen to start a new life. But you must promise me,” Henry urged, “PLEASE TEACH YOUR DAUGHTER THAT VIOLENCE IS NOT LOVE.”

Lastly, distraught but hopeful Dr. Henry asks our Security Guard to translate his unconventional wish: “If it will not hurt Alice’s ribs, I would like to hug her. Would she permit this?”

Yes, Alice agreed, broken though she was.

Gingerly, Henry and Alice rose and held each other, in a safe, warm, healing embrace.

Henry then asked for one more translation. “Please tell Alice…that THIS is what love feels like.”

Fierce compassion. Stronger than diamonds.

Protective love. Brighter than gold.

Transport from hellish abuse. Warmer than buttery copper fire.

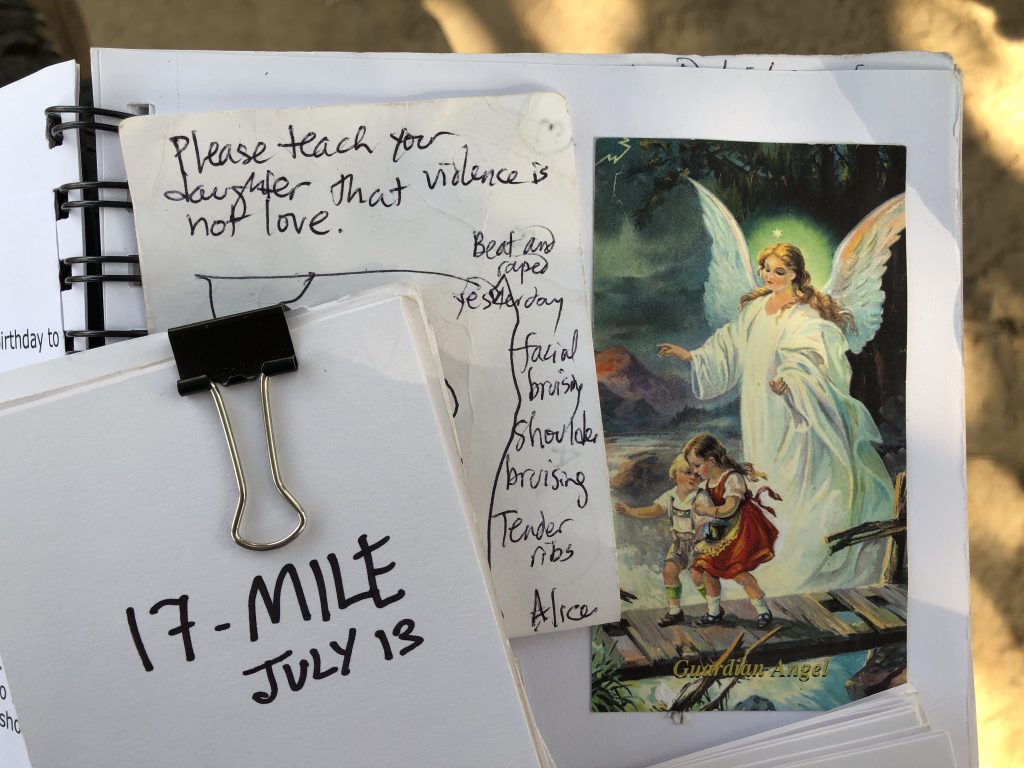

Today, the monsters of avarice and selfishness were vanquished by the guardian angels of medicine.

And today, in 17-Miles, as we traveled home in pitch black darkness on dangerous smugglers’ roads with our Zambian teammates filling the bus with heartbreakingly beautiful Bemba hymns, I can not doubt that, together, we really did Help Save the Next Girl.

Comments are currently closed.